One of the foundational beliefs in Islam is that the Qur’an has been preserved perfectly, without alteration or loss, since the time it was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad. This idea is supported by the Qur’an itself, particularly in verse 15:9, which claims that God has taken it upon Himself to safeguard the text for all time. For many Muslims, this is a matter of faith and identity, reinforcing the idea that their holy book stands apart from all other religious scriptures.

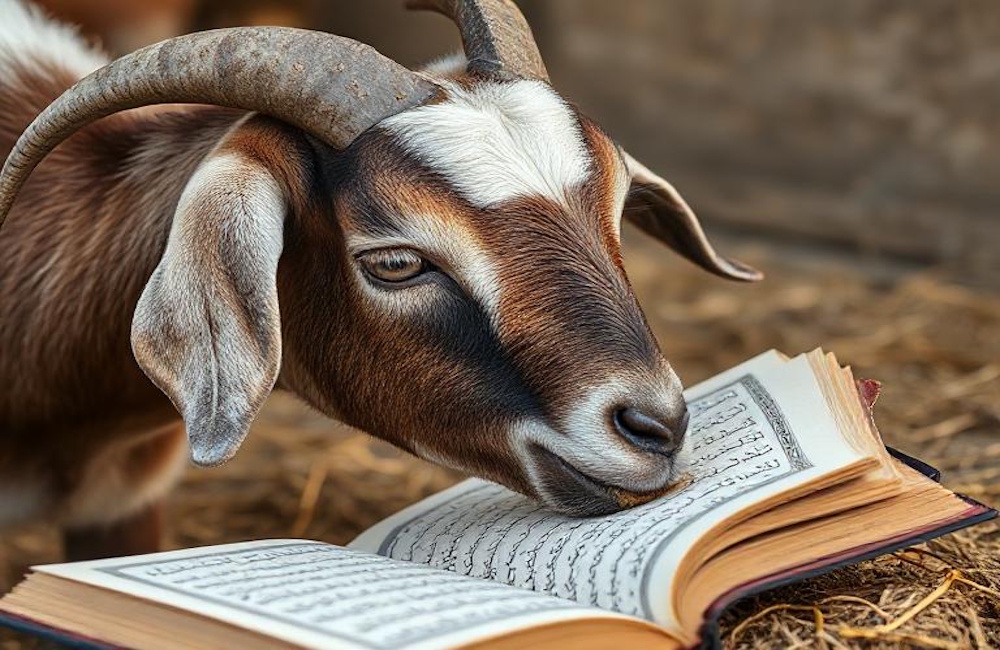

Yet within the Islamic tradition itself, there are narrations that raise challenging questions about this claim. One of the most unusual and often overlooked stories is found in several respected hadith collections. It involves a household incident, a piece of written revelation, and an unlikely intruder — a goat.

The Story of the Eaten Verses

According to a narration attributed to Aisha, the wife of the Prophet, two verses of the Qur’an — one regarding the punishment of stoning for adultery, and another prescribing adult breastfeeding as a way to establish kinship ties — were written on a piece of paper and kept under her pillow. After the Prophet’s death, while the household was occupied with funeral arrangements, a domesticated goat entered the room and ate the paper on which those verses were written. This account appears in multiple sources, including Sunan Ibn Majah, Musnad Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and the works of scholars like As-Suyuti and Ibn Qutaybah.

The Significance of the Missing Content

What makes this story particularly significant is not just the oddity of a goat eating scripture, but the nature of the verses said to have been lost. Both deal with issues that are highly sensitive and controversial even today. The verse about stoning contradicts the Qur’an’s explicit ruling on adultery, which prescribes one hundred lashes, not execution by stoning. The verse about adult breastfeeding is culturally difficult to accept and rarely, if ever, practiced by Muslims.

The fact that these two verses — out of all possible ones — are the ones that were supposedly lost raises legitimate questions. Was this simply a coincidence? If so, why were they not preserved through memorization, which is often cited as the primary method by which the Qur’an was maintained? If they were indeed part of the revelation, why do they not appear in the official compilation we have today? If they were never widely accepted, then why were they written down in the first place?

Implications for the Idea of Divine Preservation

The implications of this story are uncomfortable. If something as mundane as a goat eating a sheet of paper could result in the loss of divine revelation, then the claim of perfect preservation becomes difficult to uphold without further qualification. Some may argue that God allowed the verse to be lost because it was abrogated or no longer applicable. Others may see this as a symbolic account rather than a literal event. But either way, it suggests a far more human and vulnerable process of transmission than is often acknowledged in religious discourse.

The Historical Context of Compilation

This story also points to a broader issue in the early history of the Qur’an. The Qur’an was not compiled into a single volume during the Prophet’s lifetime. It was only after his death, and particularly after the deaths of many Qur’an memorizers in battle, that the first collection was made under Caliph Abu Bakr. A more standardized version was later produced under Caliph Uthman, who ordered the destruction of all variant versions to unify the Muslim community under one official text.

In addition, historical records show that some of the Prophet’s companions had their own personal copies of the Qur’an with slight differences. For example, Ubayy ibn Ka’b and Abdullah ibn Mas’ud reportedly had codices that included verses or arrangements not found in the Uthmanic version. This points to a more complex and evolving process of canonization than the idealized narrative of instant and flawless preservation.

Revisiting the Notion of Forgetting Revelation

The Qur’an itself makes mention of abrogation and even forgetting of certain verses. In Qur’an 2:106, it states, “We do not abrogate a verse or cause it to be forgotten except that We bring forth one better than it or similar to it.” While traditional interpretation sees this as a reference to divine will, others see in it an admission of textual fluidity, with the possibility that some parts of the revelation may have been lost, altered, or replaced during the early stages of transmission.

Conclusion

Whether one accepts the hadith about the goat as literal history or symbolic narrative, it undeniably raises deeper questions about the transmission, preservation, and editing of sacred texts. While the dominant Islamic view holds fast to the belief in divine protection of the Qur’an, historical sources and early hadith suggest a more human story — one involving writing, memory, loss, and political consolidation.